First, a note about compasses. There are compasses, and there are “compasses” that are really just a talisman at best. I’ve seen, bought (as part of a kit) and been gifted numerous of the latter. Generally speaking, if it’s the tiny thing that’s part of an inexpensive “survival kit”, or it’s attached to a whistle, on a keychain, or something of that sort, you have my permission to go ahead and make art out of it, throw it in the garbage, use it as a Monopoly piece, or whatever. You do not, however, have my permission to bet your life on its accuracy. Instead, buy a real one. Expect to pay around twenty bucks or so for an inexpensive model, twice that if you’re going to splurge. (But splurging won’t realistically get you any better performance, nor any greater usability for most hikers.) Brunton and Suunto are reliable brands, have never let me down, and are available at just about any outfitter or sporting goods store that carries camping and hiking equipment. I keep at least one in my pack at all times.

With that said… every so often on the trail, you’ll have the need to go off-trail for a moment to answer the call of nature. In the wintertime, footprints in the snow are obvious tell-tales of which way you went, and they’ll lead the way for you to get back. In the warmer months, it’s a bit more involved. As I write this, there’s still a fair bit of winter left, but that will change before long.

The nominal distance you should be from the trail is about 200 feet, which doesn’t seem that much, but consider that it’s most of the way down a football field, or twice the width of a basketball court. (Another way to experience this is to hike the Lincoln Woods trail — there are two signposts, spaced 200 feet apart, specifically to illustrate this. Find them about two miles down or so.) Now look off to the side of the trail, into the woods, and visualize finding your way back through the woods for that distance. And remember, you picked a spot where the growth is kinda thick, so you can do your thing in peace. You’re going to have to walk back through all that. This seems a silly thing to get all worked up about, but this is how Inchworm got lost. It’s right to honor her by lessons learned.

So here are a couple of strategies to hopefully get you back where you started in short order.

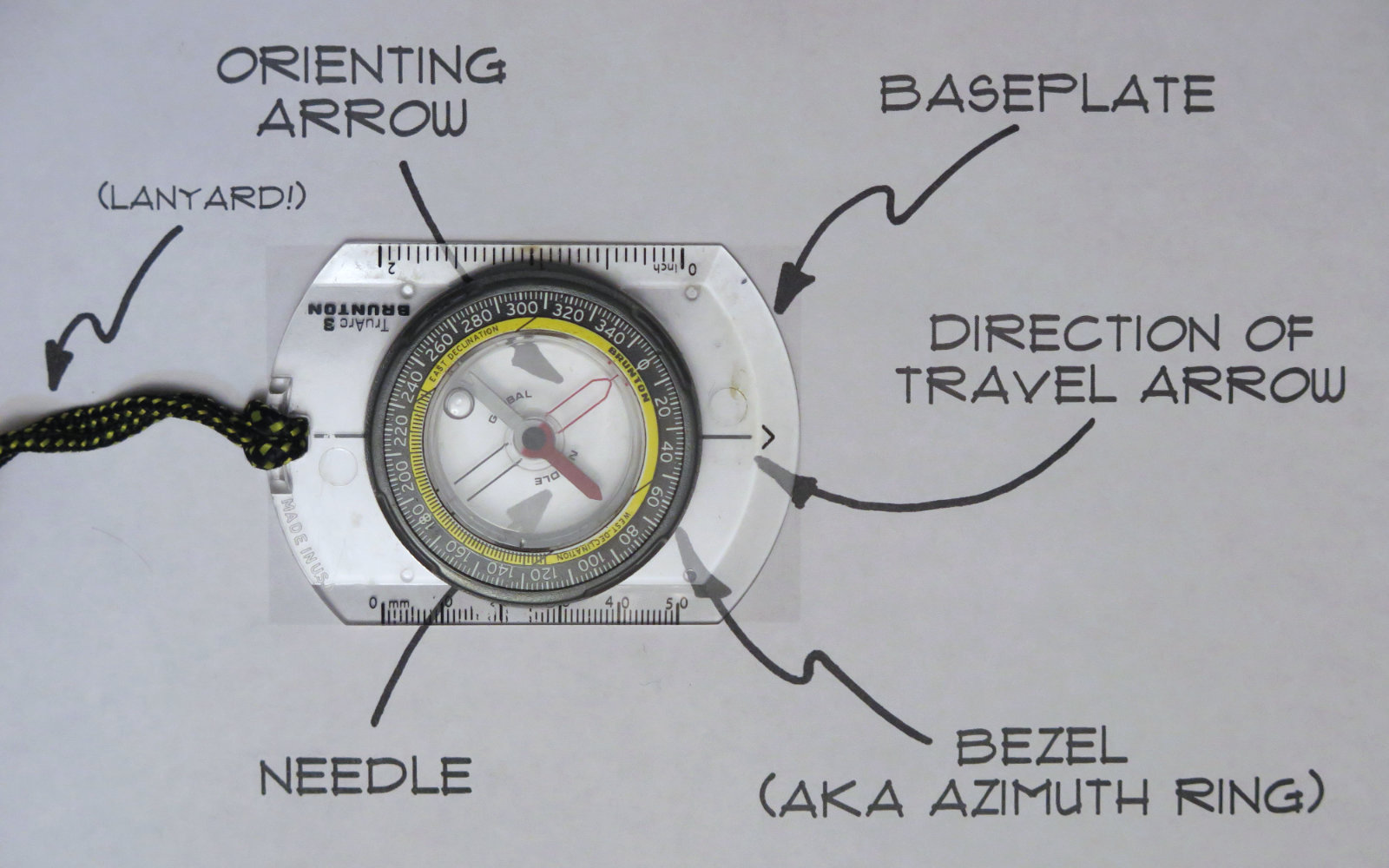

First, if your compass is in your pack, take it out and hang it from your neck by its lanyard. (If it didn’t come with one, some paracord or similar will correct this deficiency. Your compass is useless if it’s not at hand.) By now, you should have looked at the thing a few times in the comfort of your home. Ideally, you’ve already learned how to use one, or went to the website of your compass’s manufacturer and read their blurb. (Suunto and Brunton each have one, as does the American Hiking Society.)

Look around, if you haven’t already, and decide on where you want to go and do your business. Maybe you noticed some huge rocks off to the side, or maybe the trees are thicker in an area. But in the ideal, there’s some unique quirk to the landscape that’s eye catching. Raise your compass and take a bearing on where you want to go. Point the direction of travel arrow at some landmark in the distance, and rotate the bezel so the orienting arrow lines up with north (the red half) on the needle. Read off where the direction of travel arrow is pointing and memorize that number.

Now, while you do that, note its reciprocal, because that’s the direction you want to follow on the return. You went west to go into the woods? You’ll go east to get back to the trail. (If west is 270 degrees, east is obviously 90 degrees.) If you leave the bezel alone, then on the return, the “non-red” half (south) of the needle will line up with the orienting arrow, and your direction of travel arrow will point the way back. (Note: some manufacturers make south black, some make it white, some make it silver. Red seems to be the convention for marking north, however.)

Some people advocate that you grab your trowel and TP from your pack, and leave your pack by the trail so others have a sense of where to find you. But there are a couple things to think about. First, bears have been known to see “abandoned” packs as gifts from the gods. This has been a problem in Lincoln Woods, so if needed, consider a bear-hang. (Remember, a fed bear is a dead bear, and neither human nor animal deserves to die because of negligence.) However, by leaving your pack behind, others may well know where you left the trail, and where to start looking. Yet your gear, food, and clothes are in that pack, too. Instead, I would consider leaving something else as a tell-tale, and keep your pack with you. Extra bandanas are lightweight and inexpensive.

Before you set off, have a good, solid look around. Are there any interesting boulders, or maybe some birches, a huge, old growth tree, or whatever in the area? Note them, and try to create relationships between them — for example, “there’s a birch to the right of that huge boulder” — so you have some landmarks set in your mind.

Set off, dutifully counting out about 75 paces, so you’re the “approved” 200 feet from the trail, and find your spot. But don’t let counting paces get in the way of situational awareness. Bears, foxes, deer, moose, and everything else pays no heed to the 200 foot rule, and humans are dying off no faster because of it. (How many times have you stepped over a drainage, taken ten paces down the trail, and found a pile of moose exhaust? And then another one… and another one…) Do your best to leave no trace, but above all, don’t get yourself in trouble because your mind was elsewhere. Stay focused on staying safe. Everything else will fall into line as it does.

Now, I sometimes leave a trekking pole about halfway, if I can find a conspicuous spot, to keep me on the right course. Know that a trekking pole can be hard to find — amongst the trees, they blend in all too well. I’ve added some reflective tape to mine, so if I’m having a hard time finding it, my headlamp can help. Even in daylight, it makes it a little easier to spot. By leaving a trekking pole, or a bandana, or something (consider using some dead tree branches, rocks, or other things as well — just be sure to break it up on your way back) you’ve made a cairn of sorts. It’s also a good idea, as you walk, to note any fallen logs, big rocks, drainages (remember to keep 200 feet away from water) or other features in the landscape that you can use as breadcrumbs to find your way — things you might have missed on your initial survey. As well as this, look back periodically, because the forest often looks a certain way as you walk out, but can look totally different heading back. Be mindful of the land you’re walking across.

When I almost get to the place I’ve picked out, I’ll also drop a trekking pole a couple steps away, pointing back the way I’ve come. Once I’m ready to head back, I might have turned myself around a few times, but I can see by my pole which way I should start walking.

Before you start to head back, though, take your compass again, and verify your bearing. Do in reverse what you did on the way out. In our example, figure out which way is east, and remember that birch tree is now going to be on the left of that huge boulder. In the ideal, you’ll be walking in the direction that your trekking pole is pointing, and after a few moments, you’ll be back where you started, having collected your other pole, bandana, or what have you, along the way.

Now, these are just words. Declaring you’ve become an expert just by reading this post is about as effective as hanging out your shingle as a brain surgeon just because you read an A&P textbook. So go outside, into an area in which you’re familiar, and try out these skills. Maybe bring a couple friends, and make a game of it. And if you’re not getting it, then (and you’ve never heard me saying this before, I’m sure!) take a class before you head out into the mountains. In short, stay found.

As always, be careful out there.

If you enjoy reading these posts, please subscribe — stay in the loop! Your email will only be used to alert you of new posts — typically 1-2 times per week. I will not use or share your email for any other purpose without your express permission.

2 thoughts on “Ten Essentials for hiking: a snippet on how to keep from getting lost”

Great post; good ideas!

Hope you’re healing!!